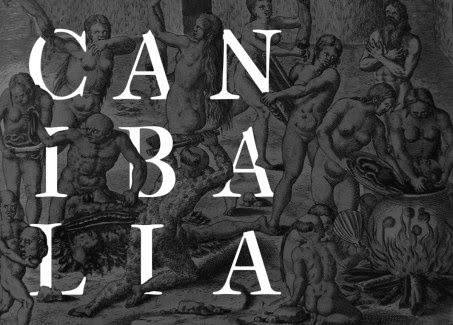

Canibalia, at Kadist Art Foundation in Paris (France) (2015)

From February 6th to April 26th 2015, Paris Kadist Art Foundation hosts the exhibition Canibalia – curated by the artist and independent researcher Julia Morandeira Arrizabalaga -dedicated to the exploration of this figure and concept through works, productions and reflections from Spanish, Portuguese and American artists.

The term ‘cannibal’ is itself a relatively recent invention that we owe to Christopher Columbus, who, during the first voyage to Americas in 1492, heard of the existence of a local population, the canibi (later changed in his diaries in caribi), dog faced and with one eye, who were likely to practise anthropophagy.

The monster of unknown and mysterious lands was thus created, and from then on would be one of the best points of intersection between nature/culture, primitive/modern, identity/otherness, that would have accompanied and justified colonial expansionism, the conquest and exploitation of the Americas, the pre-existing cultures total destruction in the name of acculturation of the wild local populations.

|

| Canibalia, exhibition view, photo: Aurélien Mole |

But, where these actually cannibals? And, in general, what meanings are associated with that word in our imagination and how are these associations created over time? The exhibition clearly reveals the dimension of fiction that, throughout history, has always accompanied instrumentally the declination and the use of this concept. Support of the Americas conquest would not have been so intense, in fact, if there had not been the bogeyman of images that are so scaring for the Western world since the days of Polyphemus, who – how strange! – had himself only one eye!

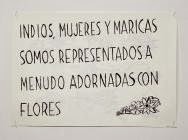

The first element of the exhibition that captures my attention is then the background on which works revealing the fictional nature of the concept will be from time to time displayed. Here the Spanish Jeleton – María Ángeles Alcántara Arpal and Jesús Sánchez Moya – has been called upon to write annotations and quotations on the walls and paint floral decorations so as to return the stereotypical context of wildness that accompanies the cannibal.

|

| Theodore de Bry, print from America 1590-1634 |

Being sacrificed, cut into pieces, butchered and eaten is one of the most common fears in 16th century Europe, and it is no coincidence that many illustrated publications of the time, widely spread in our continent, had as a subject this practice – as exemplified by Theodore de Bry volumes (in the exhibition reproduced in print) that dramatically portrayed cannibals libations, which would take place in those distant places.

Eating of human flesh becomes the trait-d’union that relates presumed wilderness of Amerindian populations with the lustful and greedy woman, thus feminising and stating as dominated by the nature the cultural Other (according to a procedure that now we know from the reflections of bell hooks), incapable of that male Western rationality terrified by the threat of being eaten, but first in yearning for engulfing the conquered.

|

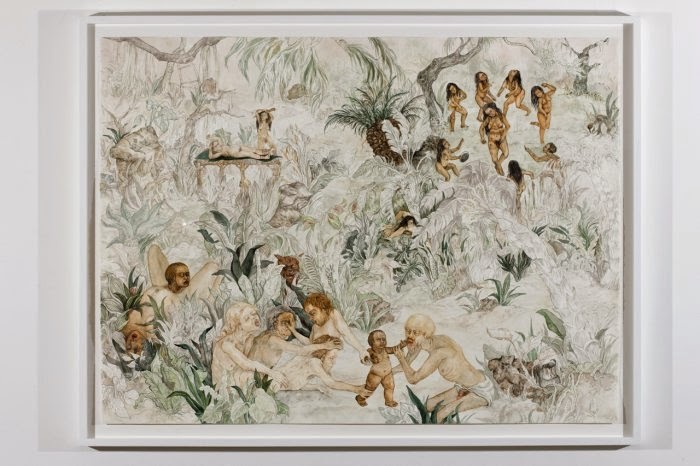

| Candice Lin, Birth of a Nation (2008) |

Hence the frequent association of the first two subjects – the woman and the cultural Other – characterised both, in the thinking of the white settlers, by perverse and extreme sexuality, as exemplified by the painting “Birth of a Nation” (2008) by Candice Lin, or by the same artist’s sculpture “Hunter Moon/Inside Out” (2015), which makes the viewers voyeurs by calling them to look inside of a sculpture in the shape of the vulva that can not not evoke the disturbing myth of the vagina dentata.

|

| Jeleton, Indios, mujeres, maricas (2014) |

An incision by the Jeleton duo itself is hosted here, “Indios, mujeres, maricas” (2014), which succinctly expresses as well this connection.

|

|

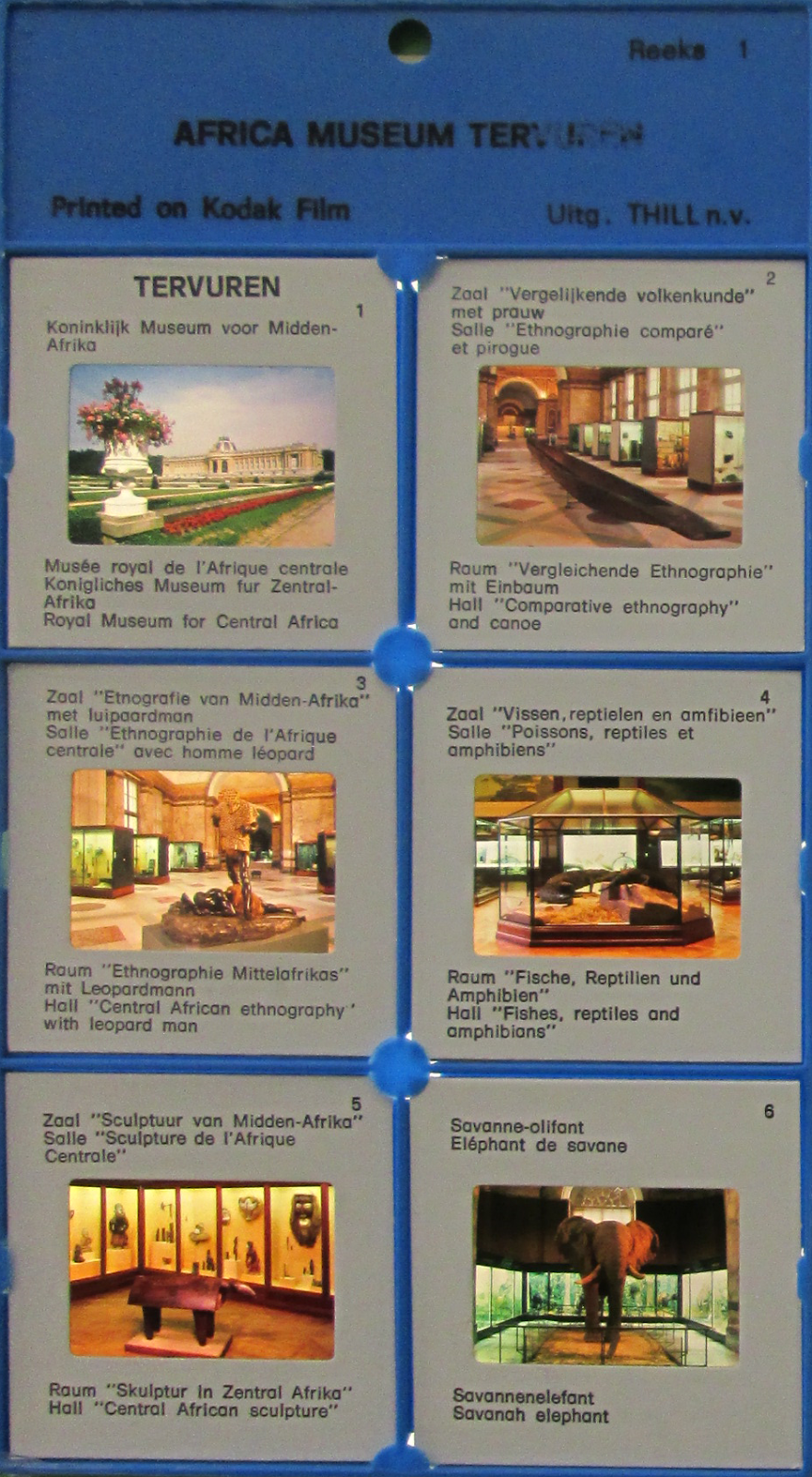

| Manuel Segade, from Countless Species |

Manuel Segade, whose research focuses on critical analysis of modes of visual representation in history, offers an excerpt of text and slides from his last book Countless Species in which discusses museums display. Here, in the first page of his work, nature and cultural otherness for what regards African populations is shown as coincident, and this explains a century of Tervuren Museum (in Belgium) success: the cannibal is here ethnographically studied, but intentionally displayed in order to exploit the sick attraction of the audience.

Yet, as the curator points out, “Since its inception, the figure of the cannibal overflows the mere anthropophagous act. And as a matter of fact, the cannibal ritual had little to do with nutritional factors. Rather, it was inscribed in warfare and vengeance. Eating the other meant eating his/her position and perspective in the world; it implied the transformation of the self through the incorporation of the other, and an understanding of society as a centrifugal force of exchange”.

|

| Runo Lagomarsino, Untitled (2010-2012), photo : Aurélien Mole |

If the opening of the exhibition is with a conceptual work by Runo Lagomarsino – “Untitled” (2010-2012), consisting in the sentence “this wall has no image but contains geography” on a blank wall – as an invitation to let us be destabilised, the ring closes with the video “Where to sit at the dinner table” (2013) by Pedro Neves Marques, in which Amerindian cosmologies are put in a dialectical relation with ecological and economic theories, so that it’s possible to draw a ‘cannibalistic’ line of continuity from colonisers-colonised relationship in the 16th century, to the Brazilian movement Antropofagia in the 1920s, to recent political claims of land rights promoted by current minority populations.

On a half way between artistic exhibition and restitution of historical and anthropological research, Canibalia vivisections the concept with the result on one hand of revealing colonial rhetoric about cultural differences and on the other to make visible the exchanges – mutual antropophagies – between different cultures in terms of specific objectives. On the other hand – reflection this last as an anthropologist – could we consider differently from a real assimilation that macroscopic as unnoticed one of the native American peoples by European settlers in North America, where these lasts appropriated of values such as freedom and solidarity of the firsts, and even of their symbols such as the eagle, and made them the quintessence of their cultural identity?

Cultural anthropophagy is then de facto part of the habitual process that – to varying degrees – characterises the mutual acculturation between different populations that at some point of their stories come into contact. Beginning thinking about the reactions in these terms means then change perspective, in a mutually interconnected world, where the balance of the system is ensured by exchange processes that require continuous adjustment in the dynamics of (economic, ecological, cultural, social, political) relationships that occur within it.

The exhibition Canibalia is a contribution in this direction.